Difference between revisions of "Tasting"

(→PALATE/TASTE: Added voice file.) |

(→PALATE/TASTE: test) |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

'''Body / Mouthfeel''' | '''Body / Mouthfeel''' | ||

| − | + | <br> [[Media:Umami.MP3|distinctive sound]] <br> | |

There are a few factors that can influence the lightness or heaviness of the body of a saké. A more robust fermentation style will result in higher extraction of amino acids and other ingredients creating a fuller body. The higher the amount of alcohol and sugar levels will also result in a heavier textural feel of a saké. | There are a few factors that can influence the lightness or heaviness of the body of a saké. A more robust fermentation style will result in higher extraction of amino acids and other ingredients creating a fuller body. The higher the amount of alcohol and sugar levels will also result in a heavier textural feel of a saké. | ||

Revision as of 19:27, 31 August 2020

| Table of contents |

|---|

There are no hard and fast rules as to how we should taste saké. But you can follow a simple guideline that professional sommeliers use when evaluating saké. It will help you gain a better insight into the type of saké you are drinking and what it has to offer in terms of your sensory experience. The following are the basic guidelines and steps that one can use when evaluating a sake:

APPEARANCE - Colour

Clear water-like or colourless - The majority of the saké in the market goes through the process of charcoal fining to remove the colour. This is why most saké are light in colour and almost water-like.

Lemon green in colour - Saké that has just been freshly pressed (the solids are removed) and has not gone through the charcoal fining process.

Light Gold /Straw (pale yellow) colour - Sakés that have gone through some light aging process. This is caused by the reaction between ingredients in saké such as amino acids, sugar and oxygen. - Sakés that did not go through the charcoal fining process called Muroka (無濾過) will also tend to have this colour.

Amber/Brown/Gold - Saké that has seen a longer ageing process like koshu 古酒 or jukusei-koshu 熟成古酒, usually but not always aged at the brewery for 3 years or more. A relatively younger aged saké that has gone through only a year of ageing will probably lean towards lighter gold than amber or brown. However, darker shades of gold, brown or amber colour may, but not necessarily indicate a fault in the saké. Normally the smell of the saké will give a better indication of whether a saké is faulty, perhaps due to bad storage conditions or contamination.

AROMAS/FRAGRANCE (Subdued - Medium - Strong)

Historically saké was made as an alcoholic beverage of taste rather than for its fragrance or kaori 香り. Due to the advent of the modern rice polishing machines, improvement in brewing technology and the discovery and usage of “aromatic” yeasts, sakés started to have more pronounced fruity and floral aromas.

The list below is not exhaustive and consumers are encouraged to discover aromatic terms that resonate with them personally, for example a memory of a smell from childhood or sensivity towards other delicate aromas.

Aged − black tea, caramel, cinnamon, cloves, honey, incense, meat broth, mushrooms, nuts (e.g. almond, walnut), soy sauce, tobacco, woody, etc

Caramel − bubblegum, cotton candy, honey, marshmallow, molasses, syrup etc.

Cereal/Grains − rice or steamed rice, rice bran, malt, oats, etc

− chestnut, although not a grain I have included it here as it tends to be associated with the sakés in this category.

Dairy − butter, cheese, milk, sour cream, yoghurt etc.

Fruity − apple, apricot, banana, citrus (e.g. lemon, orange, yuzu), lychee, melon (honey dew, rock melon, etc), nectarine, pear, tropical fruits (e.g. pineapple, jackfruit), strawberry, white peach,.

Floral/ Grass − green bamboo, cherry blossom, cut grass, lily, honey suckle, osmanthus, rose, violet, white flowers, etc.

Herbs − basil, celery, fenugreek, lemon grass, mint etc.

Nuts − almond, chestnut, hazelnut, walnut, etc

Spices − cinnamon, cloves, pepper (both black or white), nutmeg etc.

Faulty − barnyard, burnt hair, damp, moldy, musky, rotten vegetables, sticky plasters, sulfur, vineger, etc.

Sakés that use highly polished rice such as ginjo and daiginjo will tend to have higher intensity of the fruity and floral aroma spectrum while a less polished rice saké such as a honjozo and some junmai will gravitate towards the cereals/grain profile. Traditional brewing processes such as the kimoto and yamahai methods will have more dairy/lactic aromas, complex and savoury umami notes.

PALATE/TASTE

Acidity (Sanmi 総酸)

Saké contains organic acids such as succinic acid, malic acid, lactic acid, citric acid and acetic acid. Compared to saké, wines has approximately 5 times more total level of acidity and contains high amount of tartaric acid which gives wines it's sour taste. Which explains why withthout this “sourness”, consumers will find that the first taste they encounter when they sip saké is usually sweetness.

Body / Mouthfeel

distinctive sound

There are a few factors that can influence the lightness or heaviness of the body of a saké. A more robust fermentation style will result in higher extraction of amino acids and other ingredients creating a fuller body. The higher the amount of alcohol and sugar levels will also result in a heavier textural feel of a saké.

Higher polished grade sakés such as daiginjo and ginjo tend to have a lighter body structure due to its slower and cooler fermentation process.

Compared to Junmai-saké, Non-junmai sakés which has a little distilled alcohol added to enhance the aromatics of the saké will also generally have a lighter body feel due to water being added to dilute the total alcohol levels to a more palatable level.

Genshu saké or saké that received no water dilution at all after the fermentation process has a higher viscosity and textural feel.

Bitterness

Too much bitterness in a saké is generally frowned upon by consumers. However a little bitterness can help increase the taste complexity of a saké when it is well balanced with the level of sweetness.

Sweetness/Dryness (Ama-kuchi 甘口/ Kara-kuchi 辛口)

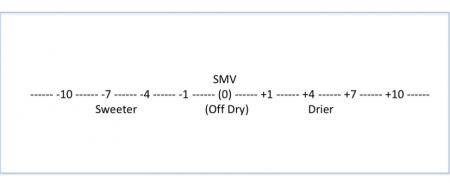

Sugar is derived from the breaking down of the complex carbohydrates of rice by the enzymatic activity of koji. There is a general sweetness/dryness measurement metric used by brewers called Nihon-shudo or Saké Meter Value (SMV) in English. You may occasionally see this value on the saké labels. Any reading between 0 to +5 is generally considered off dry (a little sweetness is detected). As the number goes higher i.e. +5 or more the saké becomes drier. In contrast, sakés with negative value SMVs becomes sweeter as the negative number grows larger. For example, kijoshu or sweet saké can have an SMV number of -30 or more. Do note that the SMV is but a very basic unit measurement of sweetness/dryness. Other factors such as the acidity, alcohol and bitterness levels will also affect how we perceive sweetness.

Umami

It is the fifth taste sensation besides bitterness, sweetness, saltiness and sourness. Saké contains a lot more umami than any other alcoholic beverage. This is because of the different types of amino acids produced during the saké brewing process. You may find certain saké labels contain information on the level of amino acids on the label (Amino sando アミノ酸度). The numerical range will usually be between a low of 1.0 to a high of 2.0. You will find sakés with higher levels of amino acids such as junmai-saké to have more umami taste than a ginjo-sake.

Finish

Once you have done smelling, swirling the saké in your mouth and finally swallowing the saké, the length of time the pleasant aromas and flavours stay and linger in your mouth is called the finish. Usually a longer finish is prefered but there are many wonderful sakés that are brewed to have a deliciously crisp and short finish called tanrei karakuchi 淡麗辛口 , an expression synonymous with brewers from the Echigo Guild in Niigata Prefecture.